Looking for ways to improve should be an expectation, not something that is optional. Whether at the individual or system level, the fact remains that there is always room for growth. So why is this the case? Pursuing improvement is a never-ending process because the landscape of knowledge, technology, and human understanding is in a perpetual state of evolution. As we advance in one area, new challenges and opportunities emerge, necessitating continuous adaptation and enhancement. The dynamism of the world, driven by scientific discoveries, technological innovations, and cultural shifts, ensures that there is always room for improvement. Each achievement unlocks doors to new possibilities, inviting a cycle of refinement and progress. Moreover, the interconnected nature of global systems means that advancements in one field often have cascading effects on others, creating a ripple effect that fuels the ongoing need for improvement.

Furthermore, the human capacity for growth and learning is boundless. Individuals and societies possess an innate drive to overcome limitations and seek better ways of doing things. This intrinsic motivation propels the never-ending quest for improvement in various aspects of life, including personal development, business practices, and societal structures. The recognition that there is no absolute pinnacle of achievement fosters a mindset of continuous improvement, encouraging a commitment to learning, innovation, and the pursuit of excellence. In this dynamic environment, embracing change and consistently striving for improvement becomes not just a goal but a fundamental aspect of the human experience. I shared the following in Disruptive Thinking:

Chase growth, not perfection.

The above quote embodies so many of the schools and districts that I have been fortunate to work with over the years, including Wells Elementary (TX), Corinth School District (MS), Davis Schools (UT), Randolph Howell Elementary (TN), Juab School District (UT), and many more. While you can read specifics by clicking on the hyperlinks above, the one common thread has been a collective belief held by all educators that improvement was and always will be a natural component of teaching, learning, and leadership.

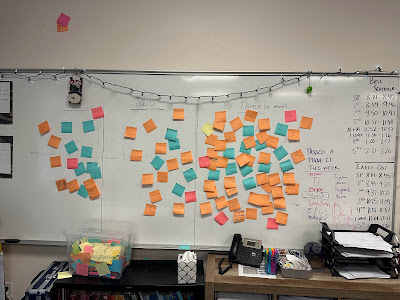

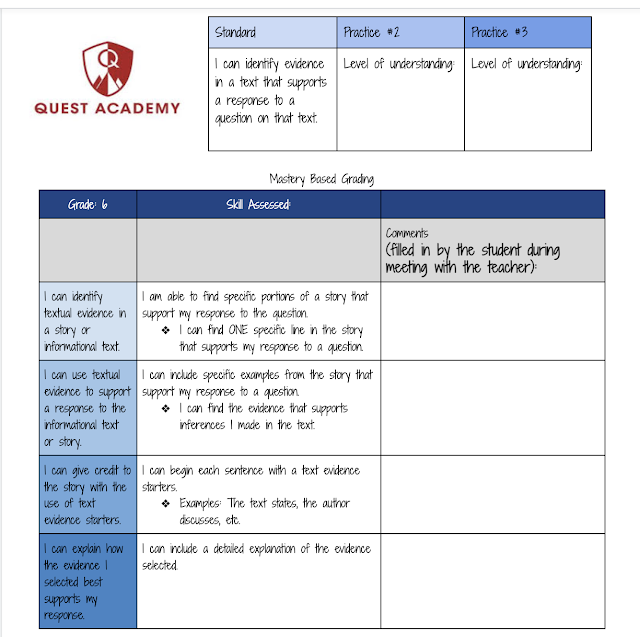

My work with Quest Academy Junior High School (UT) validates why change succeeds or fails. It all comes down to a realization that even small shifts to practice are not only doable but necessary in a disruptive world. Principal Nicki Slaugh and her staff are committed to evaluating and reflecting on their pedagogy to provide their students with the most effective learning experiences. In her words, they never settle for average. They engage in professional learning every Friday, as it is built into their schedule. You also see teachers during prep periods, lunch, and after school constantly involved in learning conversations. To top it off, at the end of the school year, Nicki leads a retreat that establishes the focus going forward.

During my first coaching visit at the school two years ago, I questioned how I could help get them to the next level as I saw firsthand the best scalable implementation of competency-based learning in the country. To put it bluntly, I was in awe. Nicki, being the visionary she is, knew exactly where there were opportunities to grow based on the Utah PCBL Framework and insights from one of my presentations she attended. From there, we worked out goals and success criteria aligned to voice, choice, rigor, relevance, co-teaching models, and inclusion. As we near the end of the partnership, more and more evidence is being collected and analyzed to show improvement in each identified area.

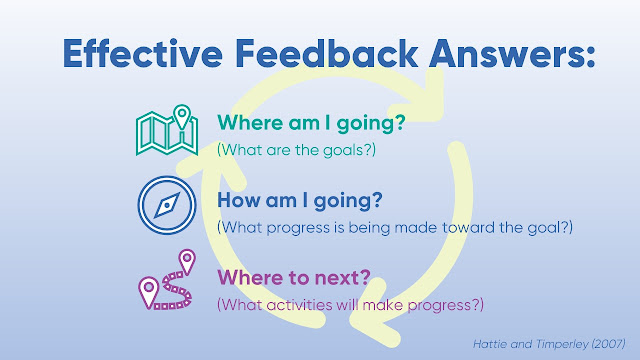

In the case of Quest, success is a collective effort, as every staff member sees the value in refining their craft. They crave feedback and aspire to be the best iterations of themselves for students and each other. When it is all said and done, I have learned so much from them and I hope the feeling is mutual. Coaching is not a one-way flow of information, ideas, concepts, and feedback. It is an organic process that enriches the learning of all involved.

The pursuit of improvement is a perpetual journey, a dynamic expedition that resonates with dedication and resilience. For educators, the path of progress is not a destination but a continuous evolution, an unwavering commitment to refining their craft and enhancing the learning experience for every student. Embracing the notion that improvement knows no bounds, educators become architects of innovation, constantly seeking new strategies, adapting to evolving methodologies, and inspiring a culture of lifelong learning. In this relentless pursuit, they discover that the true magic lies not in reaching a pinnacle but in the transformative journey of growth itself—a journey that shapes not only the minds of their students but also the indomitable spirit of the educators themselves.