“We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.” – John Dewey

The quote above from Dewey has always resonated with me, especially when I am outside doing yardwork in Texas. In the past, I used to often get stung by bees and wasps. There is a difference between the two species and how they sting. Some of them actually bite. While each encounter resulted in a painful experience, they also provided a valuable opportunity for me to reflect on why I was susceptible to stings and how to avoid them. I always learned to wear long-sleeved shirts and observe my surroundings to spot their nests. I also habitually tracked them when they were seen flying around the same areas, which allowed me to find their nests and take them out. The bottom line is that I have not been stung in a long time.

It goes without saying that experience plays a pivotal role in learning for students and adults. In Disruptive Thinking in Our Classrooms, I shared the need to provide more opportunities for this in lessons as well as specific strategies that can be used. When reflection is added, it helps to improve the connection between what has been experienced and the outcomes that were derived. The case can be made that it allows learners to go deeper into concepts while becoming more competent.

Reflection is not a simple process of introspection. Instead, it is an evidence-based, integrative, analytical, capacity-building approach that serves to generate, deepen, critique, and document learning. Developing reflective skills is central to students’ academic and professional development within a discipline. The ability to reflect on one’s practice when confronted by a novel, unusual, or complex situation distinguishes expert practitioners from novices (Schön, 1983).

Routine reflection can:

- Foster cognitive flexibility

- Aid in the construction and understanding of new knowledge

- Establish links between academic, emotional, and social experiences

- Develop essential competencies for success in a disruptive world

The outcomes listed above are supported by research:

Research has found that learning from direct experience can be more effective if coupled with reflection—that is, the intentional attempt to synthesize, abstract, and articulate the key lessons taught by experience. Additionally, the effect of reflection on learning is mediated by a greater perceived ability to achieve a goal resulting in self-efficacy.

Intentionality is key. The good news is that educators do not have to reinvent the wheel. When it comes to reflection in the classroom, the key is to make the time for it through alignment with routine pedagogy. Naturally, there is a tendency to include this at the end in the form of closure using the following prompts that can be answered using text, video, or audio:

- What did you learn of value today?

- How might you apply what you learned outside of the classroom?

- Why was this learning important to you and your peers?

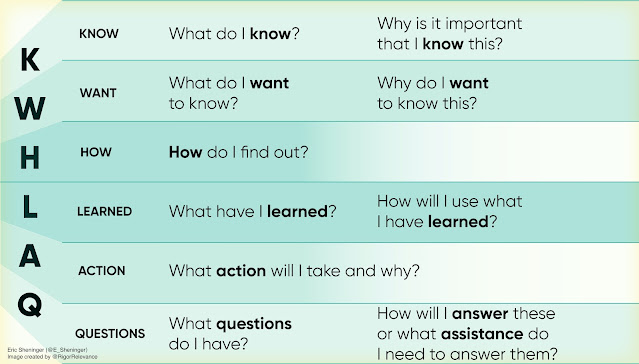

However, educators can integrate opportunities to reflect throughout a lesson. I shared the following KWHLAQ chart in Disruptive Thinking, which educators can adapt as needed.

Reflection as a part of learning is something that must be cultivated in the classroom and beyond. We can’t assume that students are familiar with this process. Thus, they can benefit from guidance to help them derive meaning from experience. Without this support, reflections may be limited to descriptive accounts of an experience or “venting of feelings” (Ash & Clayton, 2009). Experience, when reflected upon, is the best teacher.

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 1(1), 25-48.

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London: Temple Smith.